Nearly six months after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the war in the Pacific was not going well for the Allies. A terrible beating by the Japanese at the Battle of the Java Sea on February 27, 1942, resulted in the dissolving of the ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) Command and the threat of a victorious Japanese fleet sailing for Australia and possibly Hawaii. The next major encounter between the Japanese and Allied fleet, in May, was a tactical Japanese victory at Coral Sea which in turn set the stage for the Battle of Midway, which occurred from June 4-7, 1942.

US code breakers had broken the Japanese Navy’s JN-25b code, and knew that a carrier strike force under Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, the leader of the attack on Pearl Harbor, was heading for the island of Midway, which was being defended by American forces. Nagumo’s plan was to trap and then destroy the American carriers and end US presence in the Pacific Ocean. The Americans intended to ambush Nagumo’s force, surprising and destroying them in the process.

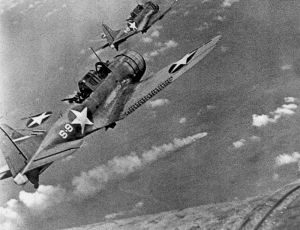

Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, had only two carriers after Coral Sea, USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Hornet (CV-8). The USS Yorktown (CV-5), in Hawaii for rushed repairs, was to rendezvous with the task force and help find and destroy the Japanese. Nagumo launched his attack on Midway Island on June 4, 1942, nearly at the same time that American planes took off from the island to find the Japanese carriers. Unfortunately, the Midway pilots were all rookies and flying already obsolete aircraft. Only 1 in 4 of the US airmen returned from fending off Japanese fighters, bombers, and ships. Still, the Japanese were impressed with the American pilots’ fighting spirit, which they likened to that of the samurai.

Admiral Raymond Spruance, aboard USS Enterprise, decided to make a huge gamble early on in the fighting. Hoping to catch the Japanese by surprise, he sent his pilots further out, all with the knowledge that they may not have enough fuel to make it back to their carriers. A Japanese scout plane spotted the Americans first, but for some reason delayed getting the message back to Admiral Nagumo. The Americans continued to search for the Japanese carriers off of Midway. They received some luck when the torpedo bomber crews spotted a Japanese destroyer that for four hours had been trying to destroy a US submarine and followed it, heading back to rejoin the fleet. Finally, the Americans had found Nagumo’s carrier group. The American squadrons had become separated from one another at some point, and US torpedo bombers found themselves without fighter cover, but valiantly attacked the Japanese carriers and released several torpedoes into the water. The torpedo bombers were promptly torn to pieces by the faster, more nimble Zero fighter planes providing air cover for Nagumo’s ships. Of 28 men flying from the Enterprise, 18 were killed. From the Yorktown, 21 of 24 pilots died during their brave attack, while only one man from the Hornet survived. None of the torpedoes launched by the American pilots hit a Japanese ship. Almost before it had even begun, the US was quickly losing the battle.

However, the fortunes of war began to change dramatically for the Americans. The sacrifice of the torpedo bomber crews provided the next wave of US dive bombers an opportunity to strike Nagumo’s force. Confident and hopeful just before the battle began, Admiral Nagumo had suddenly become indecisive and uncertain. He had wanted to launch a more coordinated attack against the US carriers, and ordered his combat aircraft patrol planes to land in order to refuel. American dive bombers, with fighter escorts this time, found the Japanese carriers and struck first. They fiercely attacked the Empire’s carriers, catching the Japanese planes refueling or just about to take off. In a matter of only five minutes, three of Japan’s carriers, the Kaga, Agaki, and Soryu, were all hit and burning fiercely. Kaga had been hit with four 1,000 pound bombs on her flight deck and hangar bay, igniting fuel and explosives from the planes awaiting takeoff. Eight hundred of her crew went down with the ship. The Agaki was hit by two bombs and suffered a similar fate to Kaga. The Soryu and Kaga were both scuttled later in the day, followed by the Agaki on June 5th. The fourth carrier, Hiryu, was still able to launch aircraft, which struck back at the USS Yorktown, and damaged the ship with three well-placed bomb hits. The Hiryu was the final Japanese carrier to be sunk on June 5th when dive bombers from Yorktown and Enterprise bombed her repeatedly.

Aboard the Yorktown, sailors were ordered to abandon ship after a series of bomb strikes caused her to list heavily to port. On June 7th, a Japanese submarine slipped through the cordon of destroyer escorts and finished Yorktown off by torpedoing and sinking her and the destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412). The US Navy also suffered the loss of 150 aircraft and 307 airmen and sailors. Despite this, Midway was an overwhelming American victory. The Empire of Japan had lost 248 aircraft, over 3,000 Japanese sailors, and one heavy cruiser. Four of the Empire’s seven carriers were now at the bottom of the ocean. It was a hard-won victory for the US, albeit one in which both sides made many mistakes. The US had not only bought valuable time to build up its Pacific Fleet, but dealt the Japanese a stunning defeat, their first naval loss since 1863.

The Battle of Midway is often cited as a turning point in World War II. While not completely crippling Japan’s navy, the US greatly wreaked havoc on the Empire’s resources. Military historian John Keegan called Midway, “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.” This single battle did not immediately end the war in the Pacific, but it was a much needed victory at the time, and one in which the US was able to build momentum from.

Five Little Known Facts About the Battle of Midway

- Some 60-70% of the American pilots that flew the various aircraft during the battle were reserve officers. According to Vice Admiral (retired) William Ward Smith, author of Midway: Turning Point of the Pacific, a fighter pilot named Ed Bassett was one such reservist that tried to pack in as much life as he could, due to a fortuneteller having once told him that he would never live beyond his twenty-seventh birthday. Having turned twenty-seven just a few days prior to the Battle of the Coral Sea, he flew raids at Salamaua and Lae and also had “several close calls” during Coral Sea as well. Bassett, like many a good fighter pilot, rushed in headlong to danger, and threw his plane at the Japanese carriers at Midway, but was never heard from again. The fortuneteller was ultimately right; if only off by a couple of months.

- Ensign George Gay, a TBD Devastator pilot with VT-8 (Torpedo Squadron 8) from USS Hornet (CV-8), was the sole survivor of his squadron of 30 aircraft. Going up against the Japanese carrier Kaga, Gay launched a torpedo which missed. Fired upon by five pursuing Japanese Zeros and anti-aircraft fire from the Kaga, Gay was wounded in the left arm, had his left rudder control blown away, and lost his rear seat gunner to Japanese fire. He briefly thought of ramming the Kaga with his plane, but decided against it and ditched in the ocean. Using a seat cushion to conceal himself, Gay watched the battle unfold, hid from strafing Zeros and Imperial Navy ships that passed so close he could see the faces of the crewmen. He went undetected and from his unique vantage point, witnessed the sinking of three of the four Japanese carriers lost at Midway. After nearly 30 hours in the water, Gay was finally rescued by a Navy PBY plane.

- Damaged during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, USS Yorktown (CV-5) was ordered to refit at Pearl Harbor to be ready for Midway. The breaking of the Japanese codes had given the Americans the upper hand. Having been told it would take 90 days to repair the Yorktown, Admiral Nimitz gave the repair workers just three to get her back in the war, which they amazingly accomplished. Yorktown served admirably during the battle, was disabled after being struck by three bombs which killed 141 sailors, and was the only American carrier sunk when a Japanese submarine sent two torpedoes into her side on June 7th.

- Three American servicemen captured during the battle were rescued from the sea, interrogated, and then murdered by the Japanese. Ensign Wesley Osmus, a pilot off the Yorktown, was picked up by the destroyer Arashi, while Ensign Frank O’Flaherty and his radioman-gunner Aviation Machinist’s Mate Bruno Gaido were picked up by either the cruiser Nagara or destroyer Makigumo (accounts vary). All three were questioned, and Osmus was soon after tied to water-filled kerosene cans and thrown overboard to drown. Admiral Nagumo only mentioned Ensign Osmus in a report that he had “died on 6 June and was buried at sea.” O’Flaherty received the Navy Cross for his attack on the Japanese invasion fleet, which curiously cites that he was killed in action on June 4th, the first day of the battle. However, a postwar investigation stated that O’Flaherty and Gaido were most likely murdered on June 15th, eleven days after they were forced to ditch in the ocean when their SBD ran out of fuel. Japanese sailors allegedly tied weights to their ankles and threw both men overboard to their deaths.

- Hollywood director John Ford served as a commander in the Naval Reserve during the war, as well as head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Considered the best director of Hollywood at the time (Ford still holds the record for Academy Award wins for directors with four); he was at Midway and captured the battle on film. Wounded in the arm by bomb shrapnel when the Japanese attacked the island, he was so moved by the American defenders and the young fighter and bomber pilots, that he made two films: “Battle of Midway,” which was intended for the American public at large; and “Torpedo Squadron,” which had been made specifically for the families of the torpedo bomber pilots, many of whom had been killed while they attacked the Japanese carriers during the battle.